Veteran Belarusian politician Mikoła Statkievič was released from prison on February 19. However, freedom came at a high price: he suffered a stroke behind bars.

Statkievič, leader of the Narodnaja Hramada Social Democratic Party, was one of 52 Belarusian dissidents liberated five months ago as part of Alaksandar Łukašenka’s deal with Washington. All those freed were taken to Lithuania, except for Statkievič, who refused to leave Belarus and remained for several hours at the Kamienny Łoh border checkpoint on the Belarusian–Lithuanian border, as confirmed by CCTV footage.

Ejsmant casts Łukašenka as a humanist

“First, I want to remind you that the decision to pardon Statkievič was taken by the president long ago,” Natalla Ejsmant, spokeswoman for the Belarusian leader, said on February 20. “But then Statkievič refused to go to the garden of Eden [Lithuania] and went back to prison.”

This is clearly a false statement. Statkievič returned to Belarus, not to prison. If he had truly been pardoned at that time, why was he taken back into custody?

When Łukašenka was informed that the oppositionist had suffered an infarction (his wife, Maryna Adamovič, says it was a stroke), “the head of state took the decision to immediately transfer Mikałaj Statkievič to a hospital, where all necessary and timely care was provided, and he was saved,” Ejsmant said.

With this remark, she attempted to portray the Belarusian ruler as a humanist. In fact, her words expose a fundamental flaw of the system: officials are unable to provide urgent medical care to a prisoner in critical condition without approval from the head of state.

It should be noted that Łukašenka was perfectly aware of Statkievič’s health problems. “The man is approaching the end,” he said in September, commenting on the politician’s refusal to leave Belarus. “He will die soon. God forbid, he dies in prison.”

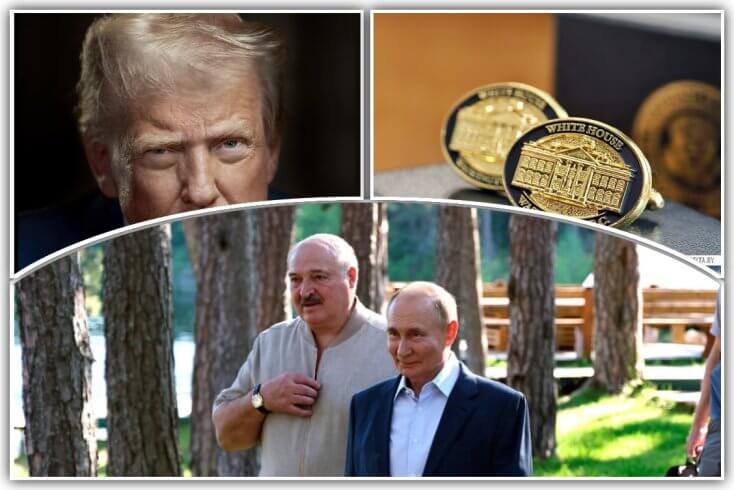

Prison officials might well have watched Statkievič die without providing adequate medical assistance. However, Łukašenka understood that a death in custody would have been a setback in negotiations with US President Donald Trump over a potential grand bargain — the release of a large number of political prisoners in exchange for sanctions relief.

This is his version of humanism.

Street fighter

Statkievič’s decision to reject exile and risk returning to prison deserves enormous respect. Those who know him well were not surprised.

A former missile forces colonel, Statkievič has been active in politics since the late 1980s. He founded the Belarusian Association of Military Servicemen, which advocated the creation of an army independent of Russian influence and the use of Belarusian rather than Russian in the army’s daily operations.

He has led Narodnaja Hramada since 1995 and is known as a “street fighter” — a leader of anti-government protests.

In 1999, he led the March for Freedom in Minsk, which drew tens of thousands of participants and ended in clashes with police a few hundred meters from Łukašenka’s office.

In 2005, he was sentenced to three years of “restricted freedom” in an open-type correctional facility for organizing a demonstration against alleged fraud in a referendum.

Five years later, he was given a six-year prison sentence for his role in a mass protest against election fraud that ended in clashes, dispersal and arrests.

Statkievič refused to ask Łukašenka for a pardon, but the Belarusian ruler released him in 2015 as he sought to improve ties with the West ahead of a new presidential election.

Statkievič was the last political prisoner to be released at that time, and he walked out of prison unbroken, claiming a moral victory over the autocrat.

In 2020, he was arrested two months before the election, as Śviatłana Cichanoŭskaja’s campaign was gaining momentum. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison on trumped-up charges. Had he remained free until August, pro-democracy forces might have had a stronger chance of ousting Łukašenka.

Pantheon of heroes

Statkievič has always taken pride in his noble ancestors — brave warriors, as he describes them. He has often stressed that he inherited good health from his father and used every opportunity in prison to exercise. However, conditions resembling medieval torture eventually took their toll.

People admire his courage. Yet not everyone is strong or fearless enough to withstand the pressure of the system as he did.

Those who ask Łukašenka for a pardon or reluctantly accept forced deportation should not be treated as second-class citizens. This, too, is a morally justified choice. When free, they can contribute more effectively to the common cause. Moreover, every human life is a supreme value in itself.

Likewise, those who advocate sanctions relief in exchange for the release of political prisoners should not be dismissed as people of elastic conscience. “Fighting the dictator until we win” may sound noble, but not everyone can survive in prison until that day comes.

As for Statkievič, he remains what he has always been: a fighter, a warrior, a knight — a hero in the pantheon of a future Belarus.